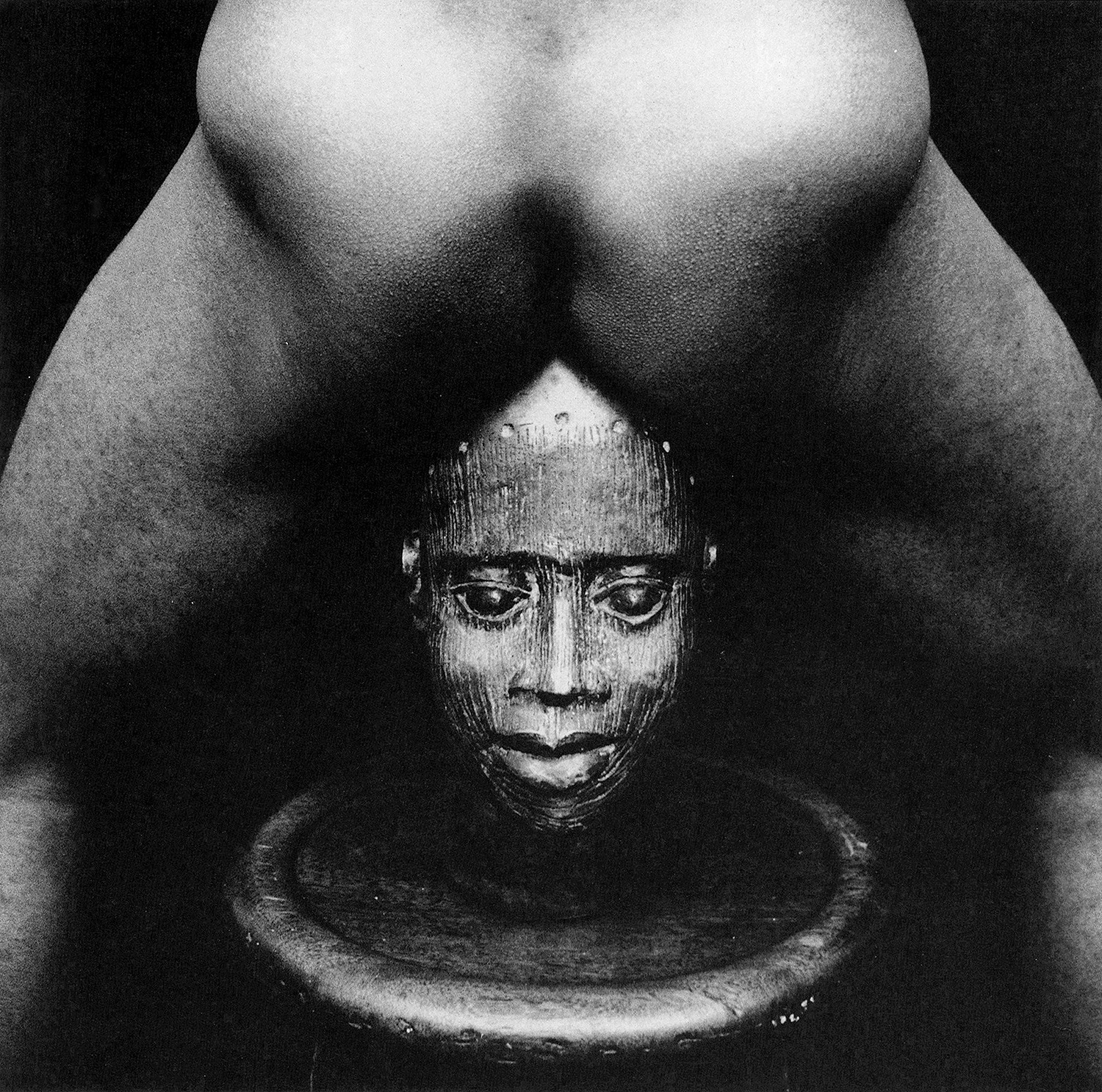

Anthropometric visions

by Simon Njami

The current approach to contemporary African art is on the same order as the anthropometric studies of the first African explorers; it's still at the stage of trying to establish a sort of typology of race and genre.

Two large symposia on contemporary African art took place this year, one in New York, organised by Susan Vogel, director of the Center for African Art, and another at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Dusseldörf, organised by Nadja Taskov-Köhler and Elisabeth Luchesi. The stated purpose of these gatherings was to draw up a prospectus on today's African art.

While the symposium held in America addressed numerous and varied issues surrounding the topic, the symposium in Dusseldörf focused specifically on Nigeria. It was clear from these events that the manner in which contemporary African art is approached in the West is tainted by an ignorance sometimes bordering on ill-will. In Dusseldörf as in New York, speakers responded to identical criteria : they came from the ranks of academia, science, museum ethnology, with a critic and a gallery-owner thrown in for good measure in Dusseldörf, as if a prerequisite to the comprehension of African art, be it of the late 20th century, was an intensive, predetermined course of study in the civilisation and history of the peoples which created it. Mercifully, at both symposia, artists were also given the floor.In Germany there were even speakers of the opinion that African art produced today belongs in ethnology museums. Alas, no one suggested whether the same could be said for art presently coming out of Europe!

Why then, does this peculiar point of view, or rather non-view, still persist, when south-Saharan artists have proven that the only criteria which can fairly be used to judge and appreciate contemporary art, be it Chinese, Japanese, Mexican or from the Ivory Coast, are the criteria of emotion and sensibility? Jan Holt, Director of the Documenta de Kassel, would say that Africa doesn't have an art history or a theory of art sufficiently well-defined to serve as a structure for discussion, and on the other hand, the discourse elaborated on in Europe since the end of the Renaissance is so context-specific that attempting to apply it to Africa would be fruitless. So where does this leave us? Is it just a question of semantics? Will the frame of reference for Africa be limited to terms like "post-colonial", "artisanal", "urban" and "functional" art? I refuse to accept this. Alas, the two symposia bore witness to the fragility of certain evidence when it's not mutually agreed on.

Before art, regardless of where it's from, can be considered for what it is and not in the prejudical terms of western art, we must affirm the legitimacy of our position again and again, for these prejudices only add to an already chronic incapacity of museums and art markets to allow emotion and subjectivity to play their role within the ever-growing classification system, further inhibiting real freedom of choice. I won't go quite so far as the Nigerian artist Emmanuel Taiwo Jegede, who became indignant at the idea that funeral statuary could possibly have been presented as contemporary African art. On the podium in Dusseldörf, he balked, 'Who would ever think of going to a cemetery in a western country looking for the essence of contemporary artistic expression?'

To my mind, these inane debates reflect the limitations achieved by today's self-styled representatives, specialists and promoters of African art : there is an objectivity problem. These people are incapable of considering a work of African art outside of the particular reference system their education and experience have saddled them with. It would be pointless to expect them to breath any sort of new life into this debate, which has only just begun.The era now before us with its trail of new complexities, holds nothing which can satisfy them, nothing they can grab on to. The world has changed too fast for what was, in the past, to remain a point of reference. We no longer judge an artist, African or otherwise, solely on consideration of his birthplace. Who could still be interested in this village, shielded from the ravages of time, if not the artist himself in his very complex and secret process of creation?

The main problem, it appears, in organising a symposium, is that one does not attend to listen and learn, but to present an autarkic science, a posited truth which doesn't hold up to scrutiny.

***

by Simon Njami

(published in the magazine Revue Noire RN04, Namibia, March 1992)

.